On the ground and in the courts, members of the Moi indigenous group are resisting oil palm expansion in West Papua, Indonesia

original source: https://chinadialogue.net/en/food/the-moi-struggle-for-land-rights/

At the northwestern tip of New Guinea, mangroves line rivers that wind their way through densely forested islands and capes. Roots sink into the water, providing a home for crabs, shrimp and shellfish, which filter water for snapper and shark. Higher up the riverbanks, deer, boar, birds of paradise and tree kangaroos live among sago palms and old-growth trees.

“No artist can bring to life so many trees. No one can create a river or plant mangroves as beautiful as this, with all the creatures that live within,” says Yance Nibra, head of Segun district in the Sorong regency of West Papua province, Indonesia.

“It’s beautiful, but it won’t be like this soon,” Yance says, as our boat passes a concrete pillar marked with the name of an oil palm company. “We’ve entered the company’s concession area.”

Yance, his family and ancestors are part of the Moi indigenous group, who are spread across Sorong’s forests and towns. When he was an official in a neighbouring district, he witnessed the damage an oil palm plantation can bring, with cleared land leaching silt into rivers and pesticides infecting the air and water. That plantation has been linked to the Fangiono family, which has ranked among Indonesia’s largest deforesters in the last few years.

A sister company upstream has been embroiled in a long-running legal battle that reached the Supreme Court earlier this year and may have wide-ranging implications for the Moi. In a decision published this month, the judges sided with local officials seeking to protect Moi claims to their ancestral lands. Last month, however, the same court sided with two other oil palm companies to the east and west of Segun, ruling that they were the victims of regulatory wrongdoing at the hands of the local government.

For more than a decade, Moi members have opposed oil palm plantations in favour of the biodiversity of rivers and forests. When local officials began backing them, the palm oil companies turned to the courts, bringing a series of lawsuits and appeals. At the heart of this battle is the issue of indigenous land rights. In an uncertain environment for indigenous peoples in Indonesia, the court decisions may pave the way to recognition for the Moi, or put up yet more barriers against it.

A regency takes the initiative

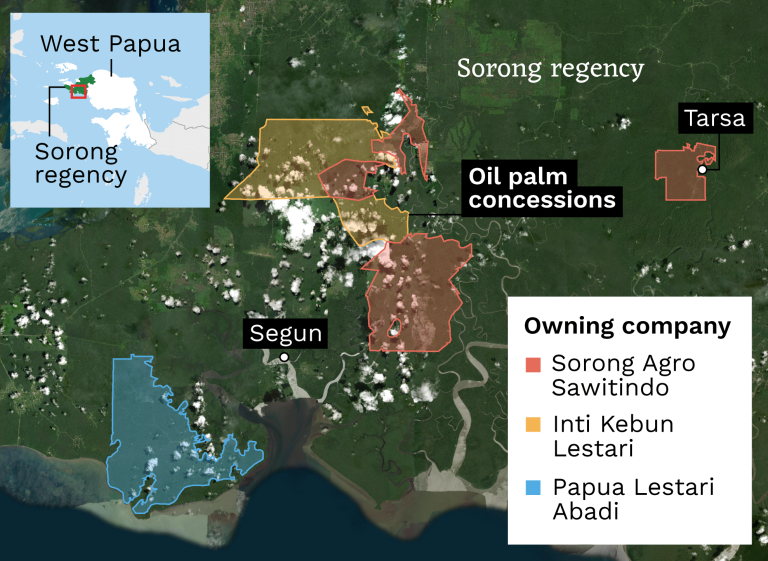

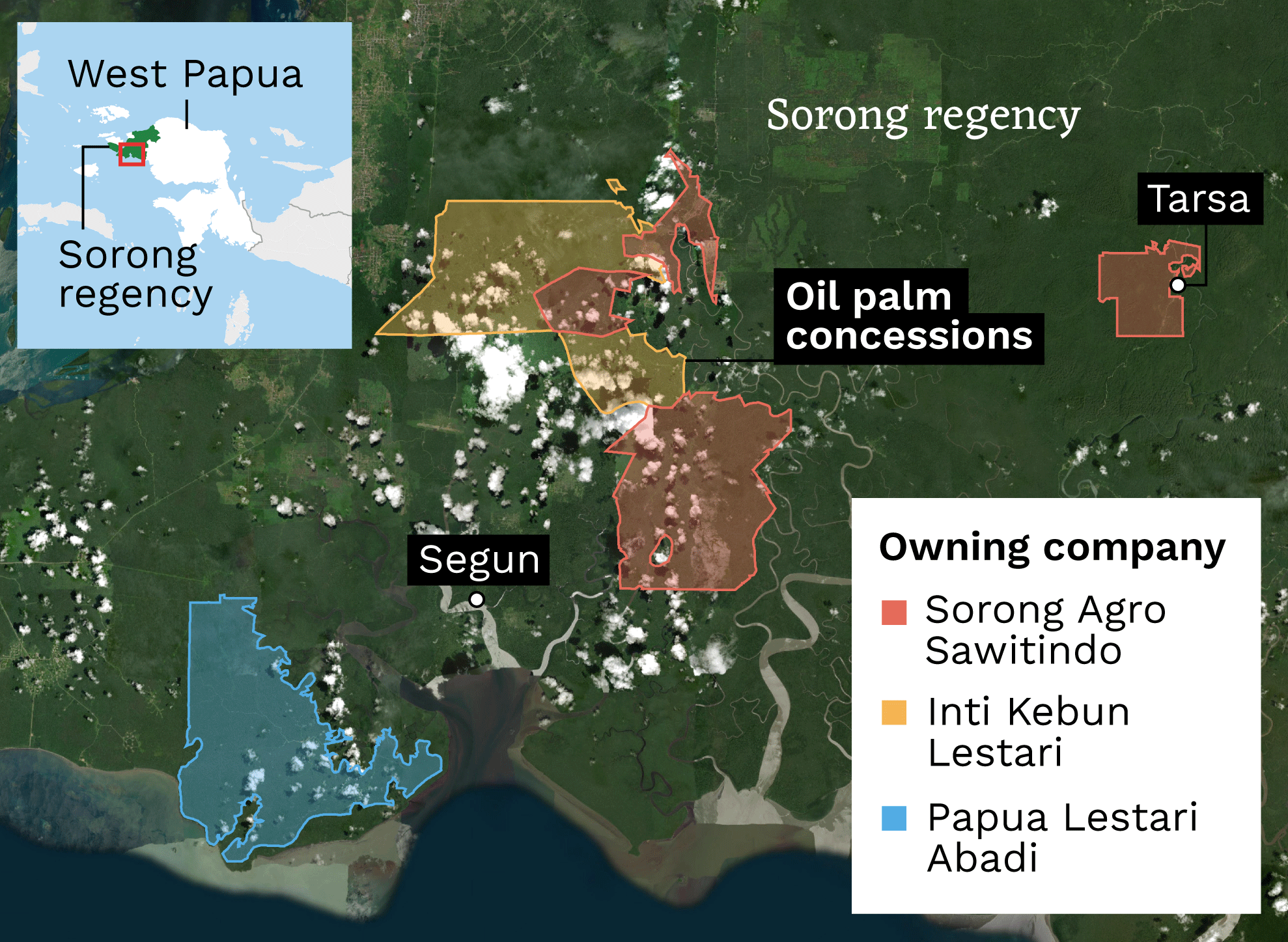

The battle began back in April 2021, when the Sorong regency government revoked the business permits of four oil palm companies. Three of the companies responded by suing the officials responsible, alleging that they had not received due warning. There’s a procedure to sanction permit holders, they said, and Johny Kamuru, the head of Sorong at the time, had not followed it.

Johny, a Moi politician who grew up living between Sorong’s forests and urban areas, said he had acted on the recommendation of a 2021 legal review of oil palm permits in West Papua province. Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission, in collaboration with local officials, had spent three years reviewing licences. It concluded that 10 companies in the province had violated the terms of their permits.

In Sorong, the licences of four companies had required they obtain the rights to the land and develop a plantation within three years. After more than seven years, they had not done either. Johny acted swiftly. Two months later, the four violators no longer had business permits.

As the companies filed their lawsuits, Moi members rushed to Johny’s support.

For many in Moi communities, the revocations were a chance to expel companies they had opposed since their permits were first awarded.

Back in 2013, when one of the companies received its first location permit, Yehud Gisim worked in the municipal police and Gideon Kilme was the head of Tarsa village, which neighbours Segun. They gathered friends and family to deliver to the Sorong government a clear letter of opposition to oil palm development.

“If you come to our area, bring destruction and demolish our yields and produce, then where are we supposed to go?” says Yehud, who is now the secretary of Konhir district. “We vehemently oppose this on principle.”

Despite the early opposition, in 2015 the Ministry of Environment and Forestry granted the company, which is called Sorong Agro Sawitindo (SAS) and is part of the Mega Masindo Group, a permit to develop in forest zones.

In all this time though, residents of Tarsa village, the seat of Konhir district, have never met a representative from SAS. One Moi leader said he hadn’t even known the company had permits to an area surrounding Tarsa until it was one of the three to file a lawsuit last year.

Gideon, who has since become the head of the Indigenous Council of Konhir district, relayed this information to the court dealing with the SAS lawsuit in Jayapura, the capital of Papua province, which handles both Papua and West Papua cases. For him, the legal action was about much more than an administrative issue. The authorities had allowed companies to stake a claim on land where people had built lives and culture.

“It’s as if they don’t know that below the trees there are people farming and hunting,” Gideon told us in his home in Tarsa. “They should visit the forest to meet with these people, so they see the forest isn’t empty, so they see the people that live there.”

In December last year, the judges in Jayapura rejected the SAS argument that the company deserved procedural warnings before losing its business permit. The following month, the same judges issued similar decisions for the two other companies. Papua Lestari Abadi (PLA), like SAS, is part of the Mega Masindo Group. Inti Kebun Lestari (IKL) is owned by the Ciliandry Anka Abadi Group, which is linked to the Fangiono family.

Concession areas belonging to the three companies involved in legal action against the Sorong government, West Papua (Data source: Nusantara Atlas, Graphic: China Dialogue)

In their decisions, the judges emphasised that Moi claims to land rights trumped the companies’ claims. They affirmed the Moi tribe’s status as a legal entity, and one whose forest livelihoods were under threat. This was critical because legal status enables indigenous groups to carry rights to their customary land, and thus to challenge the land rights companies may have obtained.

Since its creation, Indonesia has struggled to realise its constitutional promise to build a pluralist society that protects the country’s hundreds of ethnicities and their customs, in large part because of the lack of recognition for indigenous groups.

‘Our land is our culture’

One afternoon in August, when the tide had risen just high enough in Segun village, we boarded a boat with a few men in their 20s. Demi Nibra, Disyon Malalu and Salmon Sawat took us downriver, through the mangroves, to check the community’s looped ropes that trap deer and boar. Most of the ground is swamp, with up to a half metre of mud. We had to be careful, otherwise we could get stuck too.

“After two or three days, we come back to check the snares,” Salmon says. One snare had trapped a relatively large boar. With just a machete, it was too dangerous to approach an animal like this squirming with fright. Salmon once got too close and now has a disfigured finger.

But we didn’t leave disappointed, since there was enough food back in the village, and most food is shared. If they wanted more, it would only take another walk through the forest.

Disyon returned the next morning with a spear, slaughtered the boar, and sold it in a nearby town of migrants from other parts of the country. One leg can earn 250,000 rupiah, or just under US$20.

“What if we can no longer get what we need from the forest? Who would be accountable?” asks Yance, who oversees this area.

Other than the birds rustling overhead, the only sound is our footsteps in the mud. The canopy absorbs the rest, leaving the trees’ own muted breath in the wind. Malamoi, the name the Moi give to the area in which they live, is lush and varied. Long-time residents can trace the movements of animals through the forest and know where to find seasonal fruits. New Guinea has the richest plant diversity of any island, according to some scientists.

The three oil palm companies who sued the Sorong government held permits over more than 90,000 hectares – an area a little larger than New York City – more than half of which is designated as forest. The judges in Jayapura heard from half a dozen Moi who described their ties to this land.

Gideon Kilmi (standing, furthest to the left) tells the court in Jayapura about the importance of Moi ties to their land (Image: Asrida Elisabeth / China Dialogue)

Unlike the young men of Segun, Luis Fadan, 43, and Nelce Malalu, 37, don’t often go hunting. Instead, the married couple harvests sago, a pulp-like carbohydrate that is a staple food in the region, from a leafy palm of the same name. Luis plants “hard sago”, called iwakata in the Moi language, close to the village. Each palm can reach above 10 metres in height.

Luis scrapes out the insides of the trunk, and Nelce kneads the pithy fibre with water to extract its starch. Producing sago can take several days, and afterwards, the leaves and trunk can be used for construction. Although others in Segun village have begun to use machines to extract sago starch, Luis and Nelce still use traditional methods. If they sell, the sago from one palm can bring in 2 to 4 million rupiah (US$130–260).

Nelce and Luis also fish on Segun River, where the central government once built a concrete dock. Residents prefer to use smaller wooden docks for their boats, but the concrete one makes a good spot for fishing. A nearby government-built market centre also serves better as a lounge spot, because what little trade there is takes place from house to house. Village head Yahya Kutumlas says Segun’s most pressing needs are roads, secure drinking water and education.

“I’m not in favour [of oil palm plantations]. Things like that destroy nature. Then where will we find food?” says Nelce.

Lambert Kilmi and Dorkas Lobat live in the village of Tarsa, which is a two-hour drive on asphalt and dirt roads to the northeast of Segun. Here taro cultivation is plentiful. While residents have long seen the potential for taro farming to buttress a strong local economy, it began to receive support from the Econusa Foundation, an Indonesian NGO, and local officials after the lawsuits. The programme provides training to grow taro and sell it in Sorong city. After just one harvest, Lambert and Dorkas could have enough to earn 8 to 10 million rupiah (US$520–650).

Often, Moi members must rely on intermediary businesses to bring their products to market. This can leave farmers and fishers receiving lower than market prices and with financial debt, residents say. Frengky Wamafma, the head of Sorong’s Office of Food, Horticulture and Plantations, says that while companies can distribute cash directly to residents, the government focuses on training.

“The government should provide programmes and education for communities, so they can eventually become independent themselves,” he says, “and meet their needs with their livelihoods.”

Maria Syatfle grows some taro on her farm, as well as chillies, papaya, lemongrass, squash and other leafy vegetables. Schooling for her children is expensive in Sorong, so she earns extra income by crushing rocks for the construction of a new local clinic. After the oil palm companies sued, she joined a protest in solidarity with the Sorong government in a nearby village.

“We were all there – women and men from Konhir district – to fight oil palm here, because it destroys our land,” Maria said.

Indigenous rights in the courtroom

When Johny and the rest of the Sorong government revoked the permits to the oil palm companies, he told the press that he was rescuing the Moi from plantation development. Nur Amalia, a lawyer for his and the government’s defence against the companies, said the team put the Moi relationship with the forest and rivers at the centre of their arguments.

Iwan K. Niode, a lawyer for SAS and PLA, denied that the companies’ failure to build a plantation hurt the Moi villages nearby. “Where’s the harm? Is there anything that has been damaged in the forest? The forest hasn’t even been dug up and cultivated yet, and oil palm hasn’t been planted,” he said.

“The companies were issued permits, but they didn’t use them to a satisfactory standard, so the land ended up neglected. That harms the indigenous people,” Nur said. Agribusiness concessions restrict access to the land, closing off the forest that once formed livelihoods and culture.

A pillar of their defence was a local regulation document Johny signed in 2017 in which he and the Sorong government recognised the rights and land of the Moi tribe. By then, the companies had already received permits from a previous administration, but the regulation enshrined into local law that Moi have a right to be consulted and involved in any project hoping to develop Moi land. It set in motion a committee to map and convert land managed by the government into land managed by clans and sub-ethnicities. The Moi voice had been secured in Sorong, but it was just the first step toward recognition on a national level.

Since then, Moi have been creating local councils to support the collection of information for recognising land claims. They also act as local regulators to represent the tribe in dealings with outside landowners or businesses. Gideon Kilme leads the council in Tarsa, and Ishak Mili is the head in Segun.

“As the head of the [Segun] Indigenous Council, I can’t say I am prepared for oil palm to come, because the victim will be my community,” Ishak says. “Life for people here is the forest.”

Some Moi members have welcomed the arrival of oil palm and relinquished land claims to companies. They see the potential for businesses to offer jobs, raise incomes, repair roads and build schools. Companies are also required to share profits through community plantations as part of the “plasma” scheme. None of the three suing companies had established plasma plantations within the time limits stipulated by their permits, however.

Before the companies received permits on Sorong land, a local politician and timber businessman had paid for Moi members to travel to Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo, to learn from oil palm businesses there. But for Saul Malagilit, who joined the excursion, the programme backfired.

“I interviewed workers and harvested oil palm fruit, while the traditional owners of the land cried to me, because they had nowhere to go,” says Saul, now a Segun village elder. He returned home and told the regent at the time that he opposed oil palm development. The regent nevertheless went on to grant permits to several oil palm companies.

After losing their cases in Jayapura, the three companies appealed to a higher court in Makassar, on the island of Sulawesi in central Indonesia. There, the judges scolded the Sorong government for failing to issue warnings before revoking the permits, and told it to give them back.

Officials may give advance warning to companies in normal times, but these weren’t normal times, Nur said. “If it’s urgent, you can immediately revoke permits, without warning letters. And Papua’s forests are in a critical condition.”

___________

While deforestation has slowed in Indonesia in recent years, the provinces of Papua and West Papua remain hotspots for forest clearance, primarily to make space for oil palms and pulpwood.

Having exhausted much of the space in Sumatra and Kalimantan, analysts say, plantation developments are increasingly moving eastward.

With rising ocean levels, unpredictable extreme weather and acidifying seas threatening many communities across Indonesia, protecting the country’s remaining forests is key to preventing worsening climate change.

The island of New Guinea is home to the third-largest rainforest in the world, which stores billions of tonnes of carbon. Just in Papua province, the Indonesian government has issued permits in forests that would release half a year’s worth of global aviation emissions if they were cut down, according to Greenpeace.

Recent research has found that, across the tropics, indigenous lands experience less deforestation than non-protected areas.

____________

In addition, since the three lawsuits were filed, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry has rescinded more company permits. In a surprising and sweeping declaration in January this year, the ministry revoked 192 forest licences from logging, ecotourism and plantation companies. Even if Sorong were to return their permits, they may be invalid because the companies no longer have the right to operate in the forests.

“We hope that administrators at the Supreme Court can see that there are larger concerns that we can protect for these people. Investment is important, but humans are also important,” said Suroso, an expert in Johny’s regency office, before the court’s decisions were published. “We want investment that’s kind to the environment and to people, which would be native Papuans, who are rarely involved.”

What comes after the court decision?

Following the decision in Makassar, the Sorong government asked the Supreme Court, Indonesia’s highest court, to take another look at the way the law had been interpreted. In October, it upheld the Makassar judgement regarding SAS and PLA, concluding that the Sorong officials did not properly warn those two companies before revoking their permits. But in a decision published earlier this month, the court did the opposite, affirming the local government’s decision to revoke the permits of IKL.

Nur had been optimistic about the Supreme Court’s involvement, but now the way ahead is unclear. It is up to former regent Johny whether his legal team keep fighting this battle with a judicial review regarding the SAS and PLA judgement.

The seat of government in Sorong regency. The lawsuits against former regent Johny Kamuru are being heard in courts far away from here, making the process more difficult and expensive for him and his legal team. (Image: Vebrryan Hembring / China Dialogue)

Both a loss and a win at the Supreme Court level leaves much work for the Moi to accomplish before having their land rights enshrined in national law. With business permits, the companies may still apply for new forest and location permits, Iwan Niode says. But even without the companies, there are regulatory hurdles to clear.

One of the challenges when it comes to land rights is mapping the area owned by the tribe, as well as each clan. The work, which could take decades, includes sending workers to walk the area with GPS, managing land disputes with other groups and families, and persisting through the bureaucracy of multiple agencies. Often it also requires documenting the group’s heritage through its history, livelihoods and cultural artifacts.

Arimbi Heroepoetri, senior researcher for debtWatch Indonesia, estimates this could cost 300 million rupiah (US$20,000). To push for the initial regulation to recognise a tribe, costs can be more than US$50,000. But local communities often have to compete over land with large companies that have many more resources at their disposal. As such, she says the costs make the process “unfair”.

Since Sorong’s recognition of the Moi tribe in 2017, just two Moi clans of hundreds have had their land mapped. Suroso told us that the Malamoi area is not yet an indigenous forest on paper, but it is treated de facto as one. Suroso, representatives of NGOs and Moi members acknowledged the process to establish land rights was long, expensive and confusing.

“The issue is that there is little support for the government to build up the capacity to map, and there’s usually little budget to support the government on top of that,” says Silas Kalami, head of the Indigenous Peoples’ Institution (Lembaga Masyarakat Adat) in Sorong.

So far, the Sorong government has relied on NGOs like the Econusa Foundation and Pusaka, which researches and advocates for indigenous land rights recognition, to finance and conduct the mapping of territories.

After mapping, documentation and verification, it’s up to the central government in Jakarta whether to fix tribes’ and clans’ land into the national registry. Of 838 groups registered with the Indigenous Lands Registration Agency (BRWA), an NGO, 29 have fully completed the process and received certification from the central government. They inhabit less than 3% of the total area registered.

Johny completed his term in August, and although the new regent has pledged support to the Moi tribe, the temporary nature of the regent role limits the ability of incumbents to enshrine rights in law, Nur says. It may be several years before clans have the opportunity to secure land rights.

Segun residents fish by mangroves near the village. The ecologies of forest and river are closely tied, with the health of one ensuring the abundance of the other. (Image: Vebrryan Hembring / China Dialogue)

Indonesian law also allows communities to apply for social forestry permits, if they can prove that they conduct productive or conservation activities on the land. These can take the form of partnerships with companies or investment to build small businesses, and they are often much quicker than traditional indigenous rights recognition. But Franky Samperante, the head of Pusaka, says that in social forestry schemes the government only grants locals a temporary permit to conduct activities on the land.

“So communities can’t control, regulate or manage the land,” he says. “With indigenous forests, on the other hand, they have full autonomy, and they can manage it according to their ancestral knowledge and local experience.”

These two criticisms – that the process for indigenous land rights recognition is slow and other programmes don’t grant autonomy – have led advocates to push for change in the country’s Indigenous Peoples Law. Erasmus Cahyadi, a researcher with the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago (AMAN), says a bill in parliament proposes to create new paths to recognition through a court ruling and official registration, rather than a local regulation. Various forms of the bill have been in discussion in parliament for almost a decade.

“But the bill hasn’t budged from the initial discussion,” he says.

The road ahead

Erasmus has asked himself about what comes after land rights recognition. Does it contribute to prosperity? His experience suggests the benefits are small if recognition is only meant to re-categorise land or obtain management rights.

“From the beginning, we have proposed that recognition is not only to establish an indigenous forest, but also to ‘force’ the local officials to consider the indigenous perspective when they design governance,” Erasmus says.

Segun residents Yakoba Mili and Sumiati Sawat return home from collecting shellfish (Image: Vebrryan Hembring / China Dialogue)

Nico Wamafma, a Greenpeace forest campaigner in Papua, says he’s often asked if indigenous people will be able to manage the land after they’ve been given recognition. But for him, this is the wrong question to ask.

“First things first: they need to get recognition so there’s certainty that their space is theirs. The question is whether they can get their land back in five, 10, 20 or 30 years,” he says. “If they don’t do much in their area [after that] and just farm like normal, there’s no problem. That’s their right.”

“Our forest isn’t large. But what we have is enough for water and finding food. If we were to go into somebody else’s forest and take their things, we’d be met with anger. There’s no way they would let us do that,” Gideon told us in Tarsa. “What’s here is enough for us and for our children and our grandchildren.”

original source: https://chinadialogue.net/en/food/the-moi-struggle-for-land-rights/